The Challenge for the SEQRP…or any Regional Plan

In cycling they have an expression, “light weight, strong, cheap – choose two.” The reality being that you can’t have all three. The SEQRP really needs a north star, the thing that guides how we want to live, perhaps arguably not how we’re told to live. More carrot less stick.

The release of the latest iteration of the draft SEQRP is always interesting from the comments it generates throughout the professional services and government circles. Be that affordability, migration, density versus urban expansion and even whether the document is market facing or otherwise. The timing of this draft plan whilst hitting the milestone of government saying it has successfully achieved a review, quite possibly has not afforded the process the time it so deservedly needs.

The aspirational target of having 70% of new development moving to higher densities, soft density, missing middle or however you wish to describe it; is actually against the principle of improved affordability on a like for like basis. The demand for accommodation; be that rental or owner occupier, has never been stronger in the 30 years (effectively a generation) that the author has been a practicing property economist. Yet despite this demand, the ability to provide medium to higher density accommodation is not being met because the market can’t afford the construction price plus the inflated prices that are needing to be paid to amalgamate and acquire sites where this type of development is possible. So, if building up is not market facing but aspirational; and constraining urban expansion is the key policy driver, affordability will suffer. Light strong cheap scenario sound familiar?

The reality on the ground in the present cycle is that broadly speaking, only premium apartment accommodation can be delivered by the private sector. And that may be fine if we acknowledge that it is the reality of the market conditions and that those people most likely to buy that accommodation will probably have an expensive house to sell. Whilst it doesn’t solve the affordability issue, it does help achieve density, although somewhat exclusively. This needs to be acknowledged as an outcome of the SEQRP that density does come at a financial cost. It is simply more expensive to build an apartment than it is a house, made worse by the fact that many builders no longer have the desire nor the capacity to build residential apartments that have a high-risk profile compared to government sponsored work in the healthcare sector, which is dragging resources away from the private sector.

SEQ and QLD has experienced extraordinary growth over the past three years, mostly from interstate migration that is now being supplemented by international migration. As at December 2022, Queensland’s population had grown by over 116,000 for the year. The last time this was experienced was in the heady days of 2008 right before the Global Financial Crisis. The current draft SEQRP is being asked to cope with this growth that is expected to set a new annual record sometime in 2023.

So how does gentle density work when the population is growing at such a rapid rate? In theory it should work really well if one applies the only two metrics of supply and demand; but theory doesn’t always translate into reality. If you can’t build it at a price that the market will accept, it won’t have support from the financiers, valuers and buyers. This is not necessarily a nimby issue; it is simply an economic issue.

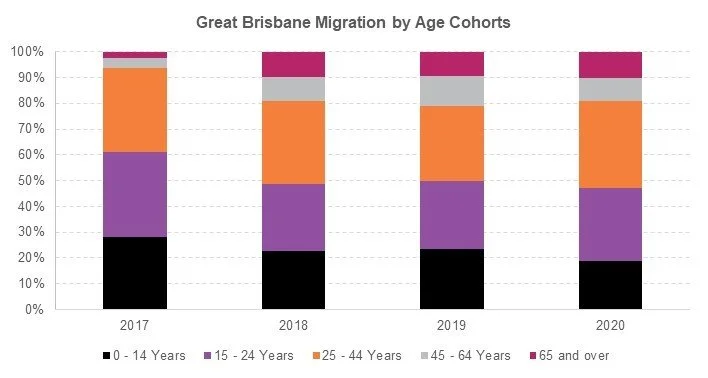

If we are to look at population migration patterns through a lens which accepts it is fluid in nature, one has to ask the question of who is moving here and quite possibly why? It is generally acknowledged that QLD’s greatest growth in interstate migration comes from NSW and more recently, VIC also chipped in with strong movement north. The most obvious lever has always been the residential price differential and to some extent this is reasonably correlated. So, when you think about that one simple concept; who are most likely to move to QLD for financial reasons? Typically, younger people.

The migration data to Greater Brisbane reflects 80% of people are aged under 45 years. This is a demographic cohort that is either thinking about having children, or in the process of raising children. It is also arguably one of the most financially challenging stages in most people’s lives, acknowledging that many on the pension or with a disability are also under financial duress.

If the premise is that building density is more expensive than detached housing for the consumer, this is a demographic that will not be overly in favour of higher costs. In addition, acknowledging that this is a migration pattern that is young, do they really want to raise a family in higher density? Whilst it can be debated about what is optimal for how children are raised, the simple fact is that if SEQ continues to build higher density, the per capita share of usable greenspace diminishes. I suspect most families with children would like somewhere close and safe for their children to shoot hoops, kick a ball, learn to ride a bike etc. Unless our legislation around compulsory acquisition changes to allow for the expansion of parklands, the author suspects many families will continue to push back against most forms of density. Having stated that, most masterplanned communities actually have the capacity to build in density around key amenity and parklands through good planning practices; the irony being that the opposition to urban expansion actually prohibits this form of development. All roads shouldn’t lead to the CBD, suburban economic centres and industrial areas continue to grow in importance as consumption and work patterns change.

As an exercise around affordability in very simple terms, the 2001 and 2021 Census periods were used to look at the median household income compared to the median house price within the respective LGA’s noted above…or pre–Regional Plan and post-Regional Plan. In 20 years, there are a lot of economic events that have occurred, the most obvious and recent being the Pandemic which lifted prices, though the GFC also dropped prices; swings and round abouts as they say. However, the author would suggest that by constraining detached housing development with a greater reliance on infill development, this has generally had an upward influence on prices. This was made worse by a very poor land monitoring model that significantly overstated what supply existed. Again, if the goal of a regional plan is to increase densities whilst reducing urban expansion, there needs to be an honest discussion about what the consequences of such actions are, both positive and negative.

Fun fact, the average age of a Queenslander is 38. Typically, an age where we raise children, juggle mortgages, work out where kids need to be for sport, ballet, band or the like – most of which are generally in locations that are not well serviced by public transport. Do most 38-year-olds want to raise a family in density? It is a fair question and one where the answer is neither black nor white, though in theory the answer is probably more in the negative than positive. Perhaps the question needing to be asked of our regional plans, is how do we make density acceptable to families whilst also making it affordable?

Having stated that, the other elephant in the room that has been impacting affordability - irrespective of what type of construction is being undertaken - is the very significant cost rise across almost all inputs. The only reason steel has declined is due to a weakening in the price of iron ore which peaked in July 2021 at more than double the current price per tonne. The cost of building new is expensive, which makes the first home buyer grant for only new product seem redundant under the current economic conditions whereby the construction sector is so overwhelmed that the policy is no longer about generating employment. Perhaps it is time for a review?

The SEQRP whilst well intended, has now been with SEQ for two decades if one considers when it was first written. Over that period of time, a lot has changed. Perhaps some context, the first I-Phone wasn’t released until 2007. A smart phone that would be considered dumb by today’s standards. Is it time we actually fully reviewed the SEQRP instead of massaging a plan that is twenty years old? A lot has changed, including how people work, where they work, how they recreate and how they want to live.

Light weight - strong – cheap; choose two. In a similar vein, is the SEQRP “affordable, higher density, quality of life, choose two?” Can one plan be everything to everyone, and if it can’t, ultimately who decides? Is it a democracy where the biggest cohort wins or something else? After two decades, it feels like now would be a really good time to step back and not rush one of the most important documents that is defining the future of those in SEQ. Put political expediency aside. It might also be a good time to revisit how we future proof against the mess which is currently the residential market throughout Australia, but often more exacerbated in one of the fastest growing regions in the nation.

Matthew Gross | Director | mgross@nprco.com.au