Interest Rates...what we're not talking about

Interest rates and inflation dominate more of our conversations with clients than any other time in the past decade. There is a general acknowledgement that an over reach in house prices for Sydney and Melbourne has occurred, and although Brisbane has slowed, it hasn’t reached the tipping point just yet. If Brisbane is true to historical form, it will probably settle shortly and maintain a state of equilibrium for a period of time. Brisbane for the past decade has been a relatively stable and sustainable market. This may not prove true if overseas immigration in Australia is increased back above 200,000 people per annum. Without question this would significantly benefit the economies of Sydney and more so Melbourne than any other cities. The conflict however is that most cities in Australia currently don’t have a lot of reserve “housing” capacity.

So here’s that rock and a hard place that the title refers to. If the RBA continues to lift interest rates in order to counter inflation, logical economic theory dictates that the economy should slow, prices should soften across all sectors and inflation is reigned in to the 2%-3% band that has governed Australia’s interest rate setting. Go too hard and a recession can ensue, go to soft and prices continue to escalate.

But here is the thing, at least in this author’s opinion. Much of the inflation that is currently working its way through the economy is brought about by “non-sticky” catalysts. Floods that have made weekly groceries more expensive, particularly fresh food. War in Europe which has contributed to the increasing costs of energy. Those costs have translated into higher fuel costs which is hurting the average Australian’s hip pocket, particularly the young, pensioners and lower socio-economic households. Covid which has slowed most advanced economies and shut down many emerging economies. Manufactured product from these countries has interrupted the global supply chain in a way most would not have predicted. A world coming out of recession which has driven up both energy and mineral resources which in turn escalates the costs of the refined product, be that steel, electrical goods etc.

There is every indication that the world economy is slowing, in fact slowing quite quickly if one was to look at China’s latest economic data. On a more local level, unemployment nationally sits below 4.0%, technically well below the full employment threshold, yet wages have gone no where. Inflation is certainly not being driven by this side of the economy.

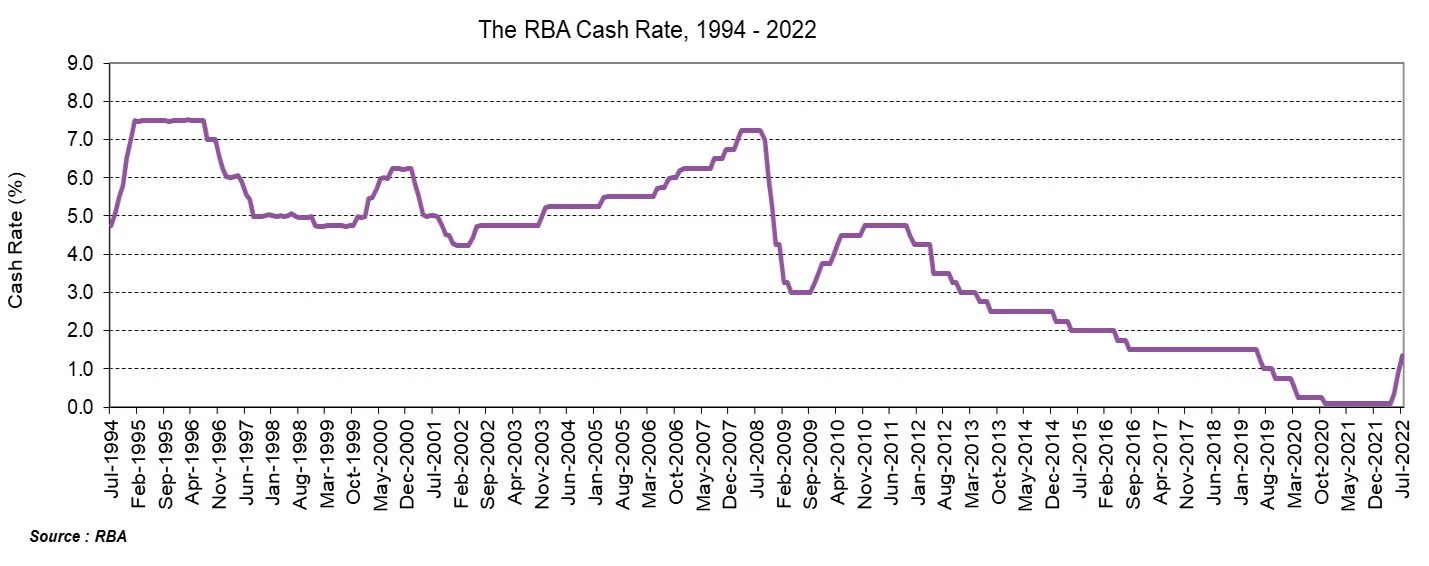

So back to the heading. Australia’s interest rates have been declining for almost a decade. That means a decade whereby monetary policy acknowledged that the national economy needed help, significant help. Here’s something to think about regarding the historical cash rate given it sits at 1.35% at the time of writing;

· The average for the last five years was 0.8%;

· The average for the last ten years was 1.53%;

· The average for the last twenty years was 3.31%.

The chances of getting back to the Baby Boomer’s 18.0% experience is hopefully left where it belongs; in the past. Again in theory, the average variable should be circa 2.5% above the cash rate of the day. At present the gap is slightly larger.

If interest rates don’t rise and Australia does go into a recession, the RBA is literally dead in the water. It will not be able to contribute in any meaningful way through monetary policy. If a recession is unavoidable in the next two years and one solution is to increase overseas migration to drive up consumption, then housing will become a significant political football. Price pressure will return, rents will continue to increase and a greater segment of society will be further polarized. Perhaps it is time for APRA to reconsider its stance on lending policies around investment loans if supply is considered to be a major social and economic constraint in most parts of Australia. Even if this does occur, do we have the skilled labour to meet this demand assuming investors become more active? The answer is an emphatic no, which means we need to increase our overseas skilled migration…which means we need more housing for these people too, which means rents go up and house prices increase as well. It is going to take some time to unwind this cycle.

Matthew Gross | Director